What I love about adventure-class motorcycles is that every manufacturer strives to find a balance between touring and enduro capabilities, resulting in a variety of unique models. Among these, the DesertX stands out as the most unusual and controversial. Many have seen FortNine’s review of the DesertX. In his review, Ryan hails the DesertX as the best adventure motorcycle. However, for me, the DesertX is far from a dream bike. It feels like everyone has received a new manual, while I’m still following an old one.

Let’s start with its merits. For those who enjoy riding very fast on mid-sized motorcycles with a 21-inch front wheel, the DesertX is the only option. It’s incredibly dynamic and maintains superb stability at speeds over 200 km/h, thanks to its sporty short-stroke engine and powerful brakes. In comparison, even the Africa Twin, with its 1100cc engine, is less dynamic.

Secondly, if you prefer motorcycles in their factory condition without custom modifications, the DesertX ranks as one of the most comfortable in its class. Considering only stock seat-windscreen options, its main competitor in terms of comfort is the Tiger 900 Rally; the rest fall short. (Remember that we consider only 21-inch front-wheel bikes for now)

However, my opinion differs when it comes to Ducati’s Multistrada V4, which I regard as the best high-capacity touring motorcycle, surpassing any 1200cc adventure bike or tourer.

Contents

Ducati Desert X engine

Now, let’s discuss the DesertX’s engine. It’s extremely dynamic, showcasing Ducati’s sporty heritage. This might seem sufficient, but let’s think a little bit. The Testastretta engine was developed by Ducati back in 2001 and was used in many Ducati models including Monster, Supersport 950, Mustistrada V2, and Hypermotard 950. Perhaps it wasn’t economically viable for Ducati to significantly modify the engine from a sport-tourer to suit a Desert X model, resulting in an enduro bike with a slightly unsuitable engine.

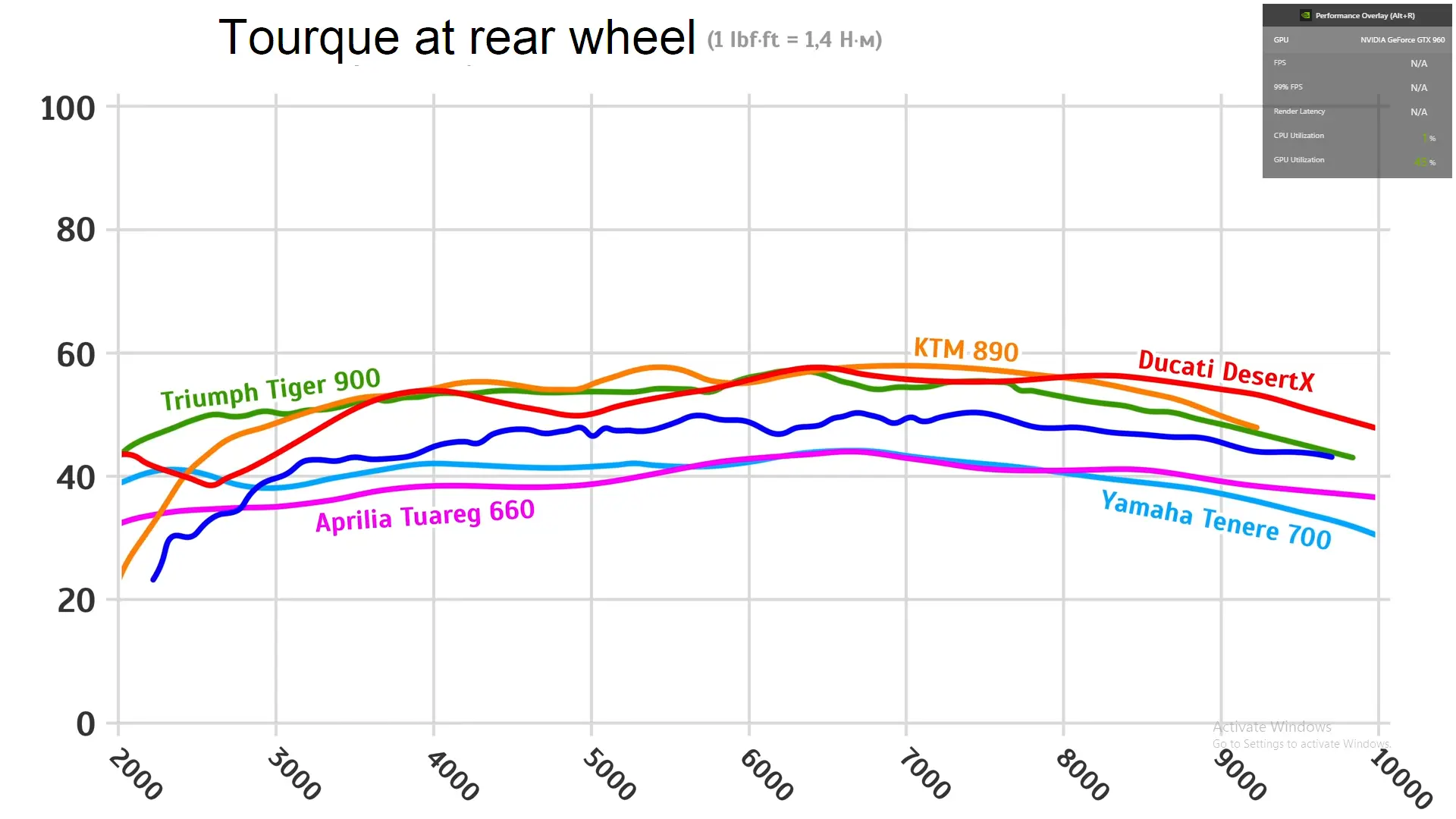

Could it be that this engine wasn’t ideal even for a sport-touring bike? The key difference between adventure and sport-tourer engines lies in the robust low-end torque, a feature typical in standard mid-sized adventure engines, which are generally unproblematic off-road.

The KTM 890 is notorious for its issues with low revs. It’s considered one of the best premium brands in the world, despite having thin low revs, mediocre real power, and a Chinese-made engine.

However, there’s now a new leader surpassing KTM in the realm of rugged low-revs. Ducati Desert X is the most powerful, yet has the worst unstable and rugged low-revs in this class, leading to unpredictable power delivery at slow speeds in technical terrain.

I don’t like it offroad since I value predictable delivery of the torque a lot more than peak power. The problem is not that it lacks power at low revs, the problem is that this power is unpredictable and hard to control. In real off-road conditions, the operating revs are usually lower and require precise traction control for every slow turn, climb, or obstacle like a large stone or log. For instance, imagine you are riding in the forest at a relatively slow speed and there is a hill with loose sand and you need to gently operate the throttle to put the exact amount of power to climb without engine stalling while avoiding excessive wheel spin. On Desert X it is very hard to do compared to Touareg 660, Tenere 700, and Tiger 900 since the engine is very unpredictable in the 2000rpm – 3500rpm range.

It’s important to understand why adventure motorcycles need stable low revs. For instance, the Tiger 1200 is less powerful than the Speed Triple, and the 1290 Super Adventure is weaker than the Super Duke, even though they share the same engines.

Even on medium-sized bikes, enduro modes fall short since precise traction control is more critical than peak power. The DesertX model lacks this finesse, offering nothing at first, then too much power, followed by a drop-off. The issue isn’t the absence of low revs but the inability to control them effectively. While one could rely on the throttle and clutch for traction control, this isn’t a practical approach for traveling in unfamiliar territories.

Ducati attempted to modify the engine for the DesertX, even increasing the compression ratio, but it was not entirely successful, and they don’t have another suitable engine. They adjusted the gear ratios to achieve slightly higher revs at low speeds in the first two gears, but this doesn’t completely address the issue.

When Ducati was developing this engine, they hadn’t even considered such a motorcycle – there was no requirement for an offroad capable adventure bike. Indeed, the very concept of a desmodromic valve system doesn’t align with the image of a rugged, low-rev adventure bike. Furthermore, in its initial concept, the DesertX was envisioned with a different engine. Besides off-road use, where else are low revs needed? In our familiar traffic jams. Similar to the Multistrada V2, the engine in such conditions is jerky and unsteady – it needs to be constantly revved up for stable operation, often requiring clutch control. The stiff clutch is another issue. It can be operated with one finger, but it requires more strength than desirable, and with the DesertX, frequent clutch modulation is necessary compared to its competitors.

But why do so many people like this engine? Perhaps they haven’t had to carry many heavy bags. Consider the conditions of the press tours in Sardinia and Colorado. These were mostly fast roads, including the smooth European dirt roads – free from traffic jams and bottlenecks. In such scenarios, where you’re riding at medium revs, the engine is superb. The mid-range dynamics are thrilling, comparable to a genuine 1000cc engine with an exhilarating acceleration effect. It’s very torquey, revs up quickly, and speeds briskly up to 200 km/h, with the quickshifter functioning excellently from the third gear at high speeds. However, the quickshifter’s rough transition between first and second gears, which is better left untouched below 6000 rpm, isn’t apparent during these picturesque rides in Sardinia. In the city, outside of traffic jams, the bike’s pull from a stoplight or its ability to overtake slow cars is impressive. For those who enjoy the feeling of dominating the road and overtaking effortlessly, it’s the perfect bike. But in heavy traffic, it becomes unpleasant. Off-road, I found it predictability lacking.

Ducati DesertX Chassis

The second significant aspect of the DesertX is its geometry. You’ve probably heard about its stability and that it has the longest wheelbase of any adventure motorcycle, regardless of engine size. Have you ever wondered why manufacturers, with decades of experience in enduro and true adventure bikes, didn’t think to increase the wheelbase? Then Ducati, with no recent history in creating enduro and dirt-oriented adventure bikes, suddenly showed everyone how it’s done.

Have you ever wondered if something is amiss here? Motorcycles have long reached optimal ranges for geometry parameters, and any deviation from these norms brings not only advantages but also drawbacks.

Yes, the DesertX is stable on straight roads, but it’s not the entire picture, and the wheelbase isn’t even the primary factor. In reality, no one deliberately aims for a long wheelbase – it naturally results from increasing the size of the motorcycle, its wheels, and its suspension. A shorter wheelbase means a smaller turning radius – great for enduro. Also, with a shorter wheelbase, you need to lean the motorcycle less at a given angle to make the same turn – again, great for enduro.

Additionally, specifically in enduro, when you have a long wheelbase, the divergence between the front and rear wheel trajectories is greater – making it harder to navigate precisely in a rut or to ride between two stones on a long-wheelbase motorcycle.

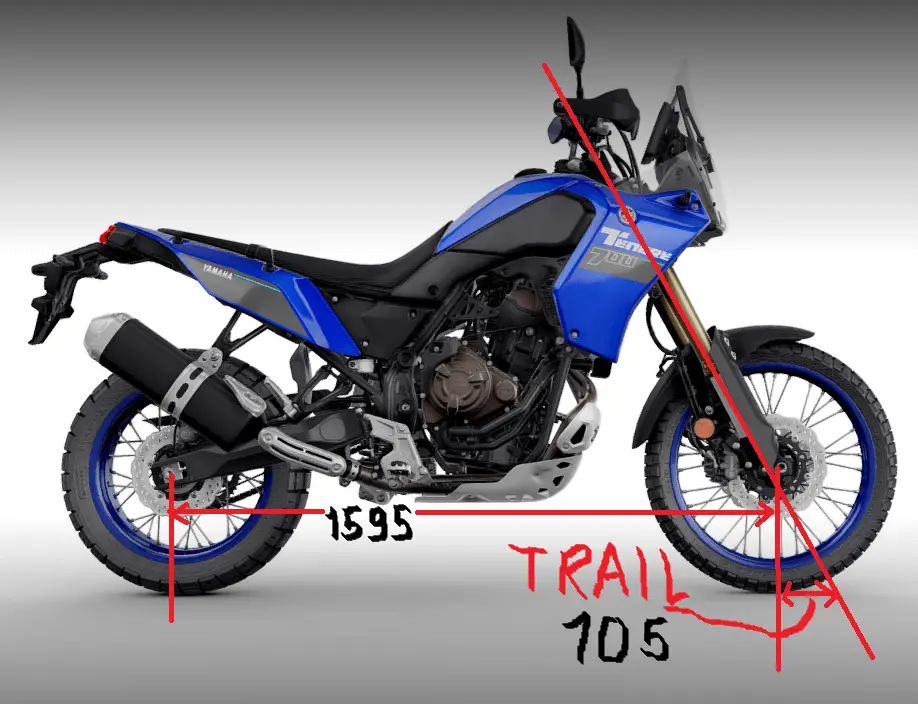

Before DesertX, the Tenere had the longest wheelbase among medium-sized adventure motorcycles. This design makes the bike more stable in terms of forward and backward swings. However, in enduro, where active weight shifting between axles is essential, this can be problematic. How did Yamaha achieve balance? Firstly, the Tenere has an ideal axle weight distribution of 48/52. Even with a long wheelbase on Tenere 700, the rider can easily shift weight forward or backward. Secondly, to compensate for the bike’s sluggishness, the Tenere has the shortest trail in its class. A shorter trail means the bike is more responsive to steering inputs and requires less effort to turn.

Despite having a sportbike-like short trail, the Tenere doesn’t feel too twitchy due to its long wheelbase – these two parameters complement each other, striking a balance between stability and agility. This scheme is similarly employed in tourers, which are inherently not short. For balance, they usually have a short trail, ensuring good steering and stability.

Another example is the 1250 GS’s remarkable performance in gymkhana. This is not only because it has the shortest wheelbase in its class but also due to the suspension features, which result in the shortest trail. This combination makes the big GS more maneuverable than any other adventure bike, almost akin to a small cc motorcycle in handling. However, in general, the trail has become a well-standardized parameter, with half of the manufacturers not even listing it in bike specifications. The majority of 21-inch front-wheel enduros and adventure motorcycles have a trail between 108 mm and 115 mm, with rare exceptions like the Tenere which has a 105mm trail.

Motocross bikes designed for wide, high-speed trails with loose surfaces can be distinguished by their trail, which may well exceed 120mm. Cruisers typically have trails ranging from 130 mm and up, while sport tourers range from 105 to 110 mm, though sometimes less. Liter sport bikes usually have trails between 100 to 105 mm, and less powerful or smaller sport bikes range from 90 to 100 mm. A trail shorter than 90 mm, for example, is found on trail bikes that aren’t designed for high speeds but can perform acrobatic feats. There’s usually not much to discuss, as almost half of all adventure motorcycles feature a 108 mm trail, which is suitable both on asphalt and off-road.

However, the DesertX unexpectedly has a 122 mm trail, which doesn’t compensate for its long wheelbase but rather exacerbates it. A motorcycle with such a wheelbase and trail can be simply described as ‘does not handle well.’ Ideally, all journalists praising the DesertX for its stability should equally highlight its lack of maneuverability, as enhancing one aspect often compromises the other. If maneuverability doesn’t deteriorate, we then face the question: why don’t other manufacturers with vast experience in creating adventure motorcycles do this? Increasing the trail is simple – just change the angle of the fork, which automatically increases the trail and wheelbase. So, the choice is between everyone else being wrong, or the DesertX having poor maneuverability.

I’ve long wondered why Ducati would design a two-wheeled tram with a sports touring engine. Curiously, Ducati usually does the opposite on most models, offering a shorter trail than competitors, resulting in more aggressive steering. The Monster with the same engine has a 93 mm trail, shorter than its competitors with the same wheelbase. Or take the Ducati Diavel; competitors have trails around 130-140 mm, while Ducati’s is 112 mm. Ducati’s sports bikes and Multistrada also have trails at the lower limit of their class.

Ducati Dakar History

So, why is the DesertX different? It was developed as a vintage bike concept, reminiscent of the 80s Dakar era. Back then, there were already adventure motorcycles with a modern trail, but there were also quite a few models with about a 130 mm trail. This helped to stabilize the bike at speed, as the longer the trail, the less prone the bike is to wobble. Also, everyone was a fan of Dakar-style riding, and Ducati seems to be emulating that. A larger trail stabilizes the bike better in the sand, requiring less handling from the rider. For instance, the rally-specific version of the KTM 450 EXC, compared to the regular version, has a longer trail.

Returning to the present, such suspensions are no longer used, the mid-size class isn’t allowed in rallies, all dynamic bikes have steering dampers, so modern powerful adventure motorcycles, if prone to wobble, only do so at extremely high speeds, and the damper typically stabilizes the motorcycle well even without an extended trail.

But overall, the DesertX seems to be designed primarily for riding on sand, as its name ‘Desert X’ suggests. One issue arises, though. Would anyone looking to journey through Africa choose a Ducati with a high-maintenance Desmo system, a 13.3:1 compression ratio, and an air filter that’s only accessible by completely removing the tank and steering damper? Among modern adventure motorcycles, the only exception where you find both a large trail and a long wheelbase is the BMW 850 GS. BMW seems to have unearthed forks from the 90s—long travel, super soft, narrow, and without adjustments. So, the engineers compensated with a long trail. The DesertX, however, doesn’t skimp on suspension, making its geometry very peculiar.

The importance of all this depends on the riding conditions. Southern Europe, for instance, is a mountainous area with 80% of the roads being twisties. There are wide and fast roads, but in rural areas, you’ll find roads that date back to the Roman Empire, where two cars can barely pass each other. These roads were not built for modern vehicles, resulting in low speeds, and sharp closed turns.

If we talk about off-road, most trails involve climbs, descents, or narrow canyons, where the speeds are low, and the paths between the stones are often so narrow that there’s hardly room to maneuver. In such conditions, a long wheelbase with a 122mm trail is as bad as it gets.

Then there’s a place like Kazakhstan, with its open, straight paths and occasional sand, where there’s no need to turn sharply and you can freely throttle up. In these conditions, the DesertX’s dynamics, geometry, and long-travel suspension are ideal. The conditions at the press shows, with wide twisty roads and fast dirt roads, are perfect for the DesertX. I would fall in love with the motorcycle if I rode it exclusively there. If off-roading for you means a long straight road with very gentle turns on dirt or sand, then yes, you will feel the bike maintains its trajectory better without the usual wobble.

However, on the narrow, winding terrain typical of mountains, the DesertX turns into a nightmare. It’s too sluggish; it’s difficult to get it to follow the intended line in turns. It turns in the right direction, but not as precisely as the class leaders. Enduro is about balance and maneuvering the bike beneath you. A bike with this geometry is reluctant to respond to such demands. On wide, fast, twisty roads, it’s also unique, but you just need to get used to it.

Naturally, the DesertX doesn’t easily settle into turns, and you need to consciously steer it. In conditions where precision and sharpness are not essential, especially on poor-quality asphalt, the ride is quite enjoyable – it feels like riding something massive yet with very good dynamics. My favorite part is accelerating out of turns, throttling up to 200 km/h. The bike moves smoothly, like it’s on rails, without twitching – a sensation not commonly found on medium-sized adventure bikes. On the highway, it rides extremely stable, not like a heavy tourer but more akin to a ship riding the waves.

Riding along the narrow, slow serpentines characteristic of Southern Europe is unpleasant – it doesn’t turn easily, requires more effort to steer, and reacts poorly to control inputs. If you think the DesertX is the epitome of maneuverability, I suggest trying at least a Tracer for comparison, and you might reconsider. So, what did I do? Enduro, trails, paths. It’s a Ducati, after all. Obviously, the DesertX isn’t striving to enter the segment of hardcore adventure bikes for enthusiasts; no one expects endurance from a Ducati. However, if we consider the DesertX without focusing on off-road capabilities, as most buyers will, we encounter several nuances. The main question is, why does a versatile motorcycle, not intended for serious off-roading, needs a 21-inch wheel and such long-travel suspension? In my reviews, I didn’t find scenarios where a 19-inch spoked wheel and more moderate suspension wouldn’t suffice. For instance, the Multistrada V2, V4, and 1290 SAS would handle the same conditions just as well, provided they have spoked wheels.

DesertX ergos

There are fundamental issues from the perspective of a simple, versatile bike. First, the DesertX’s seat is extremely high. The website lists 875 mm, while the manual says 880 mm. This height is comparable to the Tenere and KTM 890 Adventure R. However, the Tenere and KTM are, firstly, narrower in the seat, and secondly, noticeably lighter. Sure, every second Ducati buyer might be a motocross champion, but without proper enduro experience, you’re likely to drop the DesertX regularly due to its height, even if you’re tall. For a relaxed ride, a lower adventure bike is much more convenient. And if we consider crossovers, there are motorcycles with a seat height of 810 mm that fit almost everyone. For reference – at a height of 180 cm, with a correctly adjusted preload, my feet don’t touch the ground.

DesertX Weight

The second nuance is weight. The DesertX weighs 223 kg, which is impressive for a bike with nearly a liter engine. It’s lighter than the 850 GS, Africa Twin, and others. However… In any fall, the motorcycle typically hits the most conspicuous point where the metal tank and the plastic lining meet, often damaging both. Consequently, crash bars for the DesertX are essential, but this is true for almost all adventure motorcycles.

With factory crash bars DesertX’s weight reaches 235 kg according to Cycle World. For comparison, let’s take the KTM 1290 Super Adventure R, a considerably heavy motorcycle with the largest cubic capacity in the adventure class. It’s simpler with the KTM since it comes standard with crash bars and a good engine guard, weighing 247 kg on the same scale. The difference of 12 kg may not sound dramatic, especially considering that the 1290 has tanks and bars positioned very low compared to DesertX.

Reviews of the DesertX may claim that its Italian kilograms feel lighter but think practically. A very tall bike with high ground clearance, a high-mounted engine, and a high tank obviously has a high center of gravity. The DesertX lacks features like an under-seat tank, as seen in the Tuareg, or lowered rally tanks like those on the KTM, which would affect its balance. Regarding the L-twin engine, ask any owner of a Multistrada 950/V2 with the same engine, but even lower, how they feel about the center of gravity. And don’t forget that the Ducati lands flat on the ground, unlike the KTM.

Ducati DesertX luggage?

Moving on, what are adventure motorcycles for? Primarily, for traveling. For off-road travel, this usually involves a bag at the back, or frameless bags, or both. On the 1290, like almost any motorcycle, you can attach everything to the rear luggage rack or at least to a horizontal tail. To prevent the tail from falling off, you can distribute a small portion of the bag’s weight onto the back of the seat. However, the DesertX lacks both a luggage rack and a straight tail. It only has a sort of passenger handle, but a passenger willing to travel all day holding onto this handle is yet to be seen. If you need to travel with a passenger, you will also have to install handles, which come standard on most competitors, except for the Tenere.

Regarding securing the load, you might suggest that luggage can be attached to the passenger seat, and bags can also be hung there. Yes, but when you try to shift your body weight backward, you immediately find your feet resting against the side bags, or your back against the bag. But what about riding on sand, steep descents, and so on? Side bags slung over the passenger seat that don’t interfere with the guy line are small. For normal travel, you either need to install a luggage rack or side subframes – there are no other options. Let’s assume that all fasteners together weigh about 3 kg.

Ducati DeserX fuel consumption and range

Moving on, journalists often excitedly mention that the DesertX has a 21-liter tank, which is larger than the basic versions in its class. However, they often omit to mention that the Ducati consumes more fuel than others. On the highway, with cruise control set to 127 km/h by GPS most medium-sized adventure bikes consume about 4.5 l/100 km, with slight variations. Ducati consumes between 5.7 to 6.2 l/100 km. Compared to the Tuareg, the difference in similar conditions is often around 1.5 l/100 km. Even on a simple off-road, where you can ride slowly, the Ducati manages to use more than 5 liters.

According to the WMTC standard, the DesertX consumes 5.6 l/100 km, while the Aprilia consumes 4.0 l/100 km – which is accurate. Most would agree that a touring motorcycle with an off-road bias should have a range of at least 400 km. This range is optimal and tested by thousands of travelers. A range of 600-800 km is excellent, but most users will never need it; the desire for a break comes sooner, and it’s easier to carry a canister on longer journeys.

The DesertX has a real range of 320-350 km, making an auxiliary tank not just an option, but a necessity for traveling.

Ducati DesertX Suspension

The DesertX’s suspension is very good. It’s designed to be neither wobbly nor super stiff, like the 890 R or the Tuareg. Most will like it – it’s very balanced, similar to Triumph’s approach. I really like it, but like most not-too-stiff suspensions with such travel, it demands precise adjustment. For optimal performance, you need one setting for off-road and another for on-road. The preload knob is in a cramped space and requires small, incremental adjustments – not super convenient, but manageable. The rebound isn’t adjusted from the side, as on most bikes, but from behind the shock absorber, behind the protection. If you’ve been off-roading, it’s muddy, and you need to unfasten a dirty bag, bend a dirty mudguard with one hand, and crawl in with a screwdriver with the other. To adjust the compression, you must remove the seat. In real life, you’ll likely only adjust the preload, and your suspension will be set in a universal mode – not ideal for any specific use. The Tuareg, by comparison, offers a much more convenient setup. And in the Tiger 900, for example, the fork’s rebound and compression are manually adjustable without a screwdriver. The DesertX, with its engine tuned for fast riding, really lacks electronic suspension.

Ducati DesertX Wheel Issues

Another important point about why the DesertX is not ideal as a predominantly asphalt universal bike is its 21/18 wheels. The weight of tubeless rims on modern premium motorcycles is nearly the same; any difference is minimal and irrelevant when used with universal tires, which are not light. The difference is notable with tubed wheels, offering a weight relief of 1-2 kg, or with very cheap Chinese rims. Don’t expect magnesium rims with silver-plated carbon steel spokes on the DesertX – it just doesn’t make sense for a motorcycle with 21/18 wheels.

So, if you’re considering buying the DesertX primarily as a road motorcycle, here’s the problem. The new Rally STR tires are simply destroyed after just 4000km on DesertX. It is simply too powerful on the road and eats rubber fast when riding at high speeds. With the dynamics you expect from a Ducati and the speeds the DesertX allows, no off-road tires will last long. You would need to ride slower and less aggressively, allowing the tires to last longer, but then it’s unclear why you would overpay for the Ducati DesertX in the first place. 19/17-inch wheels with more rubber due to wider tires makes a lot more sense on the road for this bike. Secondly, the tire choice for 19/17 inch wheels includes sport touring tires which are not available in 21/18 inch sizes.

Like it or not, 21-inch wheels only make sense if you’re an off-road enthusiast, not for buying a motorcycle primarily for asphalt with occasional dirt riding. The 21-inch wheels don’t have a significant advantage for the off-road terrain that most Ducati owners will ride, and 99% of the time, you will experience noticeable drawbacks while riding on twisties.

Ducati DesertX Ergonomics

The ergonomics of the DesertX on the pavement are excellent. It’s clear that it’s incredibly tall, but the fit is impeccable, especially for taller riders. From an off-road perspective, it’s generally good, but there are complaints. Compared to the Tuareg, Tenere, and similar models, you’ll notice that the Ducati has a very wide seat and tank – yes, it’s more comfortable on the highway, but it’s not as convenient to stand. By the way, I’ve heard opinions that the DesertX’s seat becomes tiring quickly. This seems to depend on what you’re comparing it to. On the Tenere, 890, Tuareg, and Africa Twin, the stock seats definitely become uncomfortable faster. Out of the entire class, I’d say only the Tiger 900 has a nicer stock seat. On the DesertX, you feel it’s not completely luxurious, but you don’t start fidgeting after 3 hours; I wouldn’t be in a hurry to change it.

Another important nuance as to why the DesertX doesn’t reach the level of comfort of premium adventure bikes is its steering angle. To ensure the motorcycle with such a wheelbase and trail doesn’t need excessive space for turning, Ducati compensated with a large steering angle. Consequently, the DesertX has a very narrow windscreen, which nearly rests against the handguards on the full lock turn. The windscreen is significantly rounded on the sides, creating the appearance of a rally tower. This design doesn’t particularly affect the helmet at any speed, even in a motocross helmet. However, the windscreen is too narrow and directs the entire flow to the sides, resulting in a strong breeze hitting the arms, armpits, and shoulders. In cooler weather, this makes you stop for a hot coffee a lot sooner. This directed wind also creates a sensation of vibration in the hands. The engine itself doesn’t vibrate excessively – it’s average for its class – but the wind causes discomfort in the hands that persists long after the ride. Optional handguards come with large deflectors, which might alleviate the wrist chapping.

Windscreen

Improving the windscreen radically is not possible; a slightly higher touring version might slightly improve wind protection for the helmet area, but it won’t change the overall experience. Surprisingly, the windscreen is completely non-adjustable, which is unexpected for a premium touring motorcycle. Thus, unlike most competitors where you can choose a windscreen with excellent wind protection, the DesertX falls short. I won’t even compare it to the class of crossovers, where Multistradas are on a different level in terms of wind protection. However, the stock windscreen is decent.

Bottom Line

Beyond this, the DesertX delivers what you would expect from a premium adventure motorcycle. The brakes are excellent. The menu UI on the Ducati is consistently the best, with customizable modes, display order, new tire calibration, and navigation display options, among others. Ducati’s service philosophy is different, as it caters to those who prefer dealer servicing, unlike KTM, which is more enduro-focused and self-service friendly. KTM manuals include all tightening torques and other details. For example, cleaning the air filter on a Ducati requires removing the entire tank and steering damper, whereas on KTM 1290, you only need to unscrew four screws from the front box. Ducati’s desmodromic system also necessitates specialized servicing, making it several times more expensive. In Europe, Ducati offers a 4-year warranty and an extensive dealer network, but elsewhere, the warranty is shorter and the support less robust.

Moreover, the appearance of a Ducati, especially the DesertX, significantly affects its resale value. Even with crash bars, the motorcycle will accumulate scratches on the handguards, passenger footpegs, muffler, frame, and case when dropped. The concern for the Ducati’s appearance may prevent riders from fully realizing its potential, similar to the situation with premium scramblers – they are capable, but who would take such a beautiful bike into the forest? Additionally, Multistradas, despite being Ducatis, don’t handle hard drops as well as other crossovers.

In summary, while the DesertX offers certain premium features and an impressive aesthetic, its practicality and maintenance considerations present significant drawbacks, especially when compared to its competitors.

The DesertX is quite unique, and undoubtedly, there is a small subset of people for whom it is the ideal bike. However, I’m at a loss as to whom I would recommend it. You might say that I’m nitpicking, but if you analyze the review carefully, you’ll notice it’s structured to minimize subjective opinion. If you look at the specs on the Ducati website, you’ll find everything I’ve discussed – just pure numbers. They even have a dyno chart of the torque on their website, albeit slightly trimmed at the low revs. According to this logic, the trail and wheelbase, weight, uneven low revs, range, seat height, narrow tires, narrow windscreen, and price don’t matter as long as the bike is good. With this level of reasoning, one could even fall in love with a BMW.

I don’t consider the DesertX to be outright bad – it just objectively suits very few people. Let’s try to visualize the ideal DesertX owner: rich, tall, with an enduro background, but retired. Someone who likes to go fast in sand and mud, but without leaving Europe. In essence, I’m not sure. On one hand, I understand that most people buy adventure bikes for road riding, and from this perspective, the Ducati is superior to its competitors in almost everything, except in traffic jams. On the other hand, it’s only suitable for tall riders on asphalt. To ride off-road with such weight and height, you need significant enduro skills. And if you have these skills, you’re more likely to opt for a Tuareg or Tenere, as they feel like a scalpel off-road, while the DesertX feels more like a Swiss knife.

In contrast, riding the Tuareg off-road was intriguing, and I explored many interesting off-road routes that I didn’t even know about. Even if the DesertX cost the same as the Aprilia, I would still choose the Tuareg. But considering it’s cheaper, you could even buy a scooter for the city or an enduro for a change.

If off-roading isn’t a priority, it’s better to opt for a crossover, especially since in the DesertX’s price range, you can consider 1000 cc or even 1200 cc bikes. As a motorcycle for long journeys with a lot of cargo on light dirt roads, it’s not the best choice because there are the Africa Twin and Tenere. They are reliable, economical, and have suspensions suited for rough roads, plus they can be serviced almost anywhere. The DesertX is a weird bike, just weird.